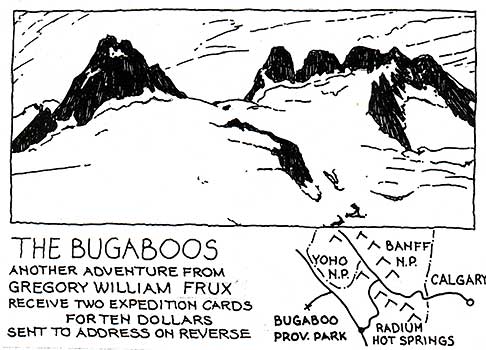

The Brooklyn-based artist Gregory William Frux is a master of adventure art in Joshua Tree, Death Valley and all over the world.

Also known as exploration art or expedition art, the practice dates to an era when documentary artists routinely accompanied major military and surveying parties. Today only a few quirky souls like Greg and his partner Janet Morgan pursue the romantic trade.

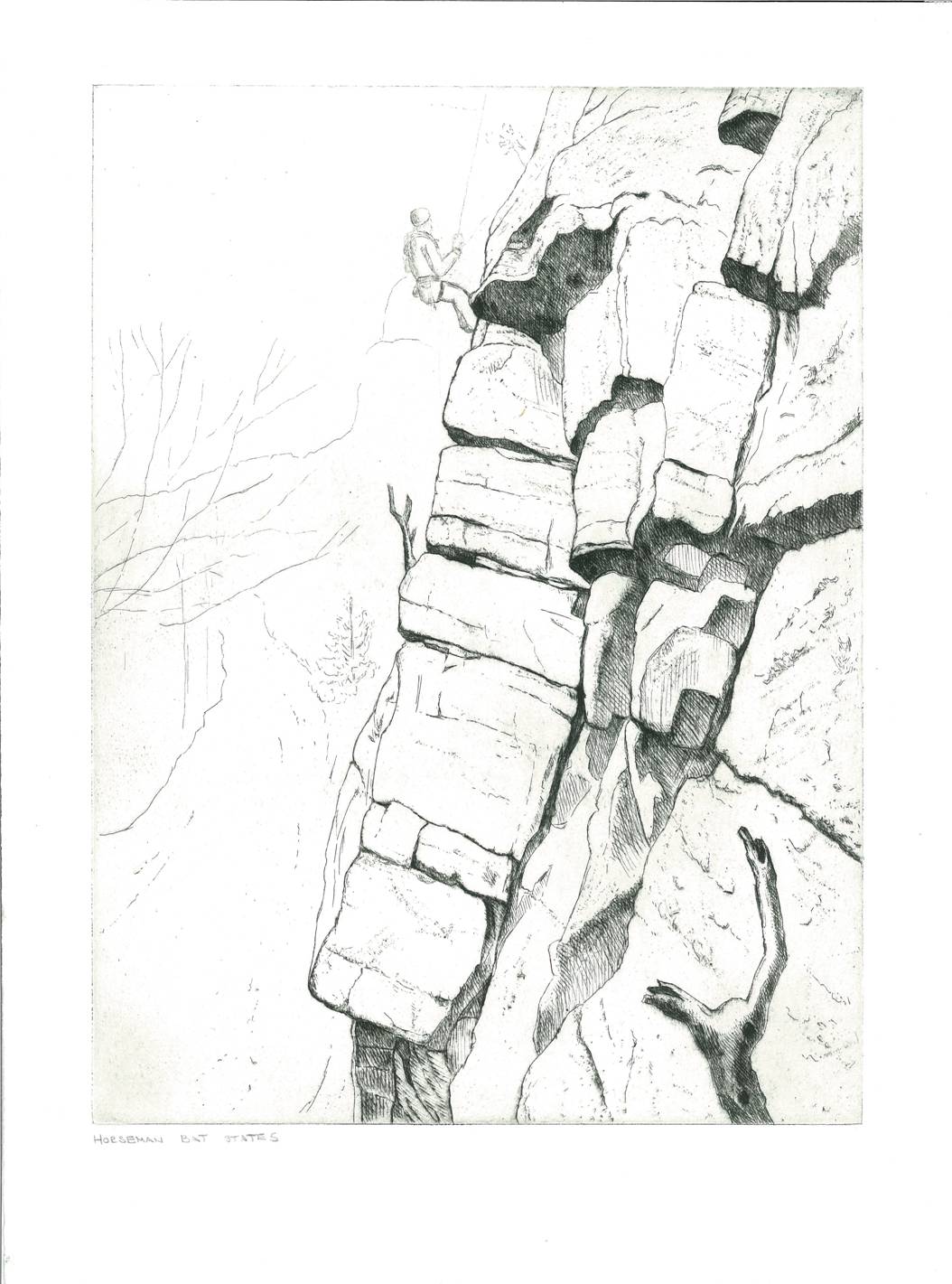

A mountaineer and backpacker, Greg has ascended 67 peaks higher than 10,000 feet. His work has been honored by such diverse organizations as the Brooklyn Arts Council, The Library of Congress, Lincoln Center, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the National Park Service. On June 20, 2013, Greg’s exhibit of etchings from the Shawangunks (quartzite cliffs in New York’s Hudson Valley) opens at the Bradford Washburn American Mountaineering Museum in Golden Colorado. In this Q and A, Greg encourages more artists to go off-road, saying there is lots more to see and record out there.

Q-Expedition artists thrived in an era when the West was being discovered and the only cameras were bulky and limiting. What is the role of the modern expedition artist now that the West is tamed and everyone has a cell phone camera?

The human eyes and brain remain vastly superior to the camera. Artists bring to the table a constellation of skills. They can discern a myriad of colors, a vast range of values–dark to light–a telescopic ability to select details and nearly a simultaneous ability to scan half the horizon. Most importantly, artists are professional observers. They are trained to select meaningful and revealing images. A good expedition artist carries knowledge of geology, botany, history etc. and can inject information into his/her work to enrich the content. In an era of a hundred million images, having a single selected image is still more valuable.

As an expeditionary artist who has traveled in remote areas of the Mohave, in Nevada and Southern Utah, I would assert that there are many untamed places remaining out there. I suspect that with ongoing climate change parts of the American West will become more harsh and difficult for humans in years to come. We live on a thin margin, dependent on oil and electricity and those resources can easily fail.

Q: Who are your favorite early expedition artists and what have you learned from them as far as technique, philosophy and attitude?

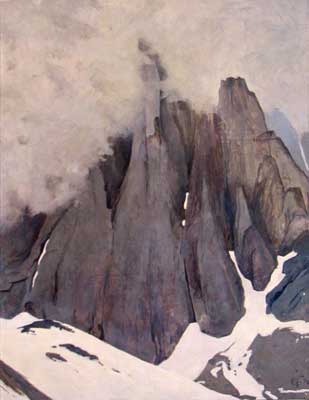

Frederic Church and Thomas Moran were both brilliant observers who created lush images on site. Each had an efficient and effective technique–Church in oils and Moran in watercolors that captured the gist of place. Both were able to carry the imagery back to the studio and create grand works–something we don’t do today. Each artist synthesized an aesthetic for areas that had not previously seemed fitting subjects for fine art– mountains, ice fields, deserts etc. I also appreciate their romantic side, as they gloried in wilderness and the forces of nature. Frederic Church’s oil sketches are among the great treasures of American art. Only recently have a group of them been installed in a place of honor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

On another note, the illustrator and engraver Edward Whymper is a hero to me because he was a cutting-edge mountaineer who also illustrated his own astounding adventures in wood block engravings. (He was the first person to climb the Matterhorn and Chimborazo).

Q: Who are some other contemporary expedition artists you might have met or know of?

James McElhinney, author and instructor at the Art Student League and a friend, is creating some beautiful travel journals. Although he doesn’t go into extreme environments, his practice is impressive and entirely consistent with this tradition. There are a number of other worthy artists whose images come to mind, but whose names I don’t immediately recollect.

Curiously, several authors come to mind immediately for vivid prose and a true spirit of adventure. One is Gretel Ehrlich as shown in her book, This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland. Another is Barry Lopez, in Arctic Dreams and other writings. The third is Craig Childs, whose has written some astounding prose on the desert Southwest.

Q: What are the places you’ve painted?

Places I’ve worked which yielded the most aesthetic rewards include: Antarctica, Arctic Norway, the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains of British Columbia, Southern Utah, Joshua Tree National Park, Death Valley National Park, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, the Shawangunk Cliffs of New York, The Sierra Nevada especially the Yosemite high country, the Cordillera Blanca of Peru, the Cordillera Real and Cordillera Occidental of Bolivia, the Patagonian Andes, Morocco, Italy and Kyrgyzstan.

I was also inspired by trips to remote mountains in Alaska and the Yukon, although conditions didn’t allow me to work on site.

Q: How do you integrate technical climbing and mountaineering with your art? Can you actually sketch while you’re on the rock? How?

Surprisingly, yes. The limiting factors are comfort and metabolism. On a mountain climb it has be warm enough to sit still outdoors and to hold a brush or pencil. This can often be the case on a mountain with established camps and especially if you have support, like a cook, porters or pack animals. In the Andes in Peru and Bolivia I did a number of oil paintings up to 16,000 feet in elevation. As long as I was in the sun, work was possible.

Clearly on a given day you can either climb or paint. It would be improbable to do both successfully. However a well-planned expedition can be more fun with rest and recovery days, which are perfect for art making. Even in difficult conditions I try hard to keep a daily journal.

I have actually planned and executed a drawing on a rock climb. It was part of my Shawangunks series, which resulted in an etching in the portfolio currently on display at the American Museum of Mountaineering. Janet Morgan suggested that I should draw a view point available only to a climber. I arranged to have a friend belay me up a rock climb 70 feet or so off the ground. I carried drawing supplies in a backpack. Once up, there was a ledge with several anchor bolts on it. I secured my harness to bolts and hauled up the climbing rope. This allowed me to safely execute the drawing at my leisure. When I was done I packed up the gear and rappelled to the ground.

Q: What is the role of the natural sciences in your art (geology, botany, archaeology, etc)? The sciences played a big role in early expedition art…how about today?

I believe that the more you know about a location, the better art you can make about it. For some people the influence on the art will be indirect. For me knowing geology is core. Just this year, such knowledge helped me to pick out repeating patterns of river meanders carving the Navajo sandstone in the canyon country of Southern Utah. Depending on your destination and your sensibilities, different disciplines will be more important. I just love learning and feel that the natural sciences deepen my appreciation in a general way.

Q: If I want to do an art expedition, how do I set my goal? Hasn’t everything already been explored?

Find some place you are intensely curious about. Collect stories, read books and articles, study maps looking for the “blank” spots, listen and dream. There is so much planet out there and so many ways to observe it– the light in Antarctica, a dry lake bed in the Mohave, a boulder field in the Sierra, a storm in New Hampshire’s White Mountains… Visual exploration is endless. Certainly, the planet has been well mapped and humans have touched most significant points on earth. But have we really looked at these places? Quiet, mindful observation can yield results anywhere–but especially in a place that takes considerable effort to reach.

To speak about this from another view point: We recently visited Southern Utah for the sixth time. As part of our trip we contacted the environmental group The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) and asked their advice to locate landscapes that were not well represented by art or photography. As advocates for wilderness protection they use this kind of material for their advocacy work. SUWA quickly replied to my query with five locations accessible with a regular car. Burr Point, in particular was a remarkable find. An 11-mile drive on a rough dirt road took us to a vista of multiple canyons–carved land, stretching eastward for thirty miles to the Colorado River. It was a spectacular, significant view, well worth painting. Is it a known location? Certainly. Has it been explored? In some ways no.

Q: What should I take along, as far as art supplies, shade tarps and anything else?

Well, I do teach a five day workshop on this. First of all, you need to bring knowledge of how to stay safe and comfortable in extreme environments. Supplies would include warm, layered clothes, with at least one more layer than you expect to need, sun protection, insulation from the ground, food, lots of water, maps and an emergency kit. Remember to use available resources. If you are at cabin or are car camping use the building or vehicle to be more comfortable. Stay well fed and hydrated. Learn about micro climate–areas of stillness and warmth can be found even in challenging environments. Topographic maps are helpful in visualizing landscape and anticipating visual opportunities. Field guides can be useful and I especially like well-written geology books addressed to a specific locale.

I like lightweight art supplies. My most compact set up is a bound sketchbook with good quality paper, a box of pencils, sharpener and erasers. Remember to bring extra supplies so that loss of a tool won’t wreck the trip. Protect the sketchbook with one or more Ziploc bags. I own a portable oil painting set called a Guerilla Painter Box, which has become core to my expeditionary practice. I paint on prepared masonite panels which fit in the box until dry and have been giving me consistently excellent results. Janet has a similarly compact set up for watercolors.

Q: What should I be looking for once I’m there?

Perhaps the question should be “How should I be looking…” I find when I am walking into a landscape an open and receptive mind is key. It is very helpful to walk by yourself if possible. If not, it is helpful to curtail random conversations that are off the topic and stay in the here and now. Early morning and later afternoon tend to have more revealing light. Often the best times come after the tent is set up! Try to cultivate the mental state friendly to experience. Sometimes that won’t come easily and good results can be achieved from just sitting down and starting to draw.

Q: How do I approach the art itself? Make sketches? Watercolors? Keep field notes?

Find techniques that match your temperament. You want a medium that will let you record your experiences quickly and responsively. I carry different tool sets for different applications. For very fast work I carry a bound sketchbook journal and some drawing pens. When I have more time I carry two drawing pads– one Bristol Board for pencil drawings and a pad of grey charcoal paper for tonal drawing with charcoal pencils and chalk. I choose the pad that best suits the subject matter. For base camps and car camping I like to have my oil painting kit, which I mentioned previously. It is important to find supplies that work for you. The very first step would be keep a field journal and just accept whatever you put in it–notes, sketches, cartoons, maps, diagrams, doodles–as the beginning of the creative process.

Q: How do I deal with the elements and stay safe?

If you are headed somewhere for an art expedition, be diligent about researching conditions and correct seasons to visit. I had two trips in the Andes (Colombia and Ecuador) where the weather more or less shut down all creative work and much of our climbing. Bring the appropriate gear, with some extra. Have a plan to extract yourself if things go wrong. I carry rescue insurance offered by the American Alpine Club. Research guide companies with a rigorous interview process–they should respond clearly and completely to email queries. Get recommendations and check other travelers’ experiences.

There are few hazards specific to making art. Being distracted is perhaps the biggest issue. Consider your location before starting to work: Are you in danger from rock fall, avalanche, lightning or flash flood? Could a car accidentally hit you? Will you be warm enough to sit for several hours? I generally make myself invisible to other people, both for safety and to limit distractions. Overall art making is a pretty safe activity.

I’ve had several accidents in my house from inattention, but none in the wilderness. OK one exception– there was the time in Joshua Tree I was eating nuts while painting and the nuts started to taste really odd. I looked down to see that I was eating ants as well as nuts… but that was the only time.

Q: What do I do once the expedition is over?

Treasure and protect your work! It is a record of a profound and unique life experience, especially in a world where experiences are increasingly moderated through digital media.

Q: Where do you plan to go next?

I’m not certain but I am kind of dreaming of climbing the second-highest peak in the western hemisphere, Ojos del Saltado (Chile, Andes), and keeping an illustrated journal.

For more on adventure artists Gregory Frux and Janet Morgan:

For more on Greg’s exhibit opening June 20, 2013 in Colorado, see:

Those Joshua Trees are the hardest, nastiest things to paint of all time. You are brave to have included them since leaving them out and concentration on the amazing rock formations and desert floor makes a plenty interesting/dynamic composition.

This is one of the richest, most eloquent and fascinating interviews on art I have read. You are a brilliant interviewer, Ann, and your subject, Greg Frux, is a multi-dimensional being whose creativity is layered all the way down to the marrow. He continually reminds the reader/artist of the source of our work: our inner posture, our ways of noticing and seeing, our attitude and relationship to the environment.

Regarding well-worn wilderness vistas, “…but have we really looked at these places?” Having just read “A Woman On Paper” (Anita Pollitzer) Greg’s inquiry re-iterates the core of Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting soul. And, what an excellent adventure artist! the paintings are beautiful and powerful.

My word, Constance, what a nice comment! I agree that Greg is brilliant in his approach to life and work. Thanks for the reminder, also, to look at the Anita Pollitzer book on Georgia O’Keeffe.