One hundred years ago Cabot Yerxa scraped a dugout into a clay bank, claiming a 160-acre homestead on a patch of sand alive with wind and water spirits. (Today we call them energy vortexes.) He spent $10 on a burro, Merry Xmas, then later built a Hopi-style pueblo of 35 rooms, now one of the most beloved handmade houses in California.

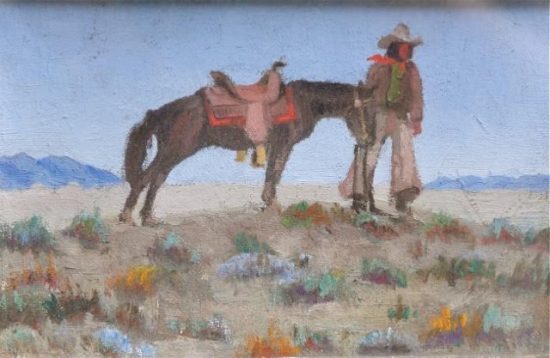

Cabot’s painting of Seven Palms oasis, though there are eight palms. Courtesy of Cabot’s Pueblo Museum.

Desert-dwellers know this story. But you might not know that Cabot traveled with a sketchbook and paints strapped to his burro. You might not know that he was pals with Jimmy Swinnerton, Agnes Pelton and Carl Eytel, or that he attended the Students Art League in LA (an incubator of modernist artists), and the Académie Julian in Paris.

“I do other things to eat, but art is my main interest,” he told Willie Boy author Harry Lawton in 1956. Cabot’s now-forgotten mission was to start an artists’ retreat on Miracle Hill, now the home of Cabot’s Pueblo Museum in Desert Hot Springs.

From Cabot Yerxa’s sketchbook. All images–unless noted–are courtesy of Lauren Segawa, Cabot’s Pueblo Museum, City of Desert Hot Springs.

Cabot pursued a lifelong career as a painter of the desert and Indians; he sold paintings throughout his life. Yet, mysteriously, only a scattered sampling of his work has ever surfaced. In recent years, Cabot historians Richard Brown, Peggy Portemour, Pat Larson, Judy Gigante and Barbara Maron have worked to restore his identity as an artist, and to turn up more of his work.

It was Maron who alerted me to Cabot’s art career, when I went to hear her speak at the Rancho Mirage Public Library in 2011. It was the first time I’d heard Cabot identified as an artist, and the first I’d heard of Theosophy, an esoteric religious movement.

A membership card found in Cabot’s wallet at the time of his death. Courtesy of Cabot’s Pueblo Museum.

Cabot had studied Theosophy since he was a young man, an interest that put him in league with many famous artists including Wassily Kandinsky (a pioneer of abstract art), Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee and Cathedral City’s own Agnes Pelton. Canada’s Group of Seven–landscape painters recently popularized by actor Steve Martin–were also influenced by Theosophy. Ever since Barbara’s talk, I’ve been thinking about Theosophy and the role it played in desert art.

Though it’s not a familiar term to many of us today, Theosophy once was as popular as Pilates. In the late 1800s, the charismatic Madame H.P. Blavatsky inspired a surge of followers for the mystical belief system. The movement later infiltrated the desert via artists trained at Lomaland, the Theosophist compound at San Diego’s Point Loma.

There is no simple way to describe Theosophy–a predecessor of the modern New Age movement–and I won’t even try. We do know that artists schooled in the doctrine wanted to drill down to “the essence of things”, as the Theosophist-sculptor Constantin Brancusi put it. Many of them naturally turned to the desert where essences are more readily seen, without all the smog and shrubbery. And it was to the desert Cabot Yerxa turned, after his family’s citrus ranch in Riverside failed due to a historic freeze.

As the familiar story goes, he hiked in from the Garnet railroad (now the Palm Springs rail station near Indian Ave. and I-10), carrying only a quart of water. He found a spot with 132-degree mineral water bubbling under the sand. With his 1913 homestead claim, Cabot had essentially discovered the place that would become Desert Hot Springs.

One day he went hunting for his lost burro and ran into the original desert-hermit artist, Carl Eytel, camped at Seven Palms oasis. The two became friends. They sketched the desert together, visited Cahuilla Indian neighbors and dined on canned milk and cold pancakes.

Yerxa had been drawing since he was a boy on the North Dakota prairie (he was born in 1883). He formalized his interest in art in the early 1900s, when he attended The Students Art League of Los Angeles and befriended co-founder Hanson Puthuff–an artist known for his desert scenes.

To further his art education, Cabot traveled to Europe in 1925. His travels are documented in the 400-page illustrated diary he kept while touring and studying at the Académie Julian. You can read excerpts in the book Cabot Yerxa Adventurer, available at the Museum.

Starting class on July 27, 1925, he wrote: “Each new student has to treat the whole bunch to chocolate and rolls in a queer little shop in rue du Dragon…The students are mostly French and are noisy; they sing, whistle, shout, throw clay, dance, smoke and otherwise act perfectly at home….everyone does as he pleases in every way.”

Back at Miracle Hill in 1941, Cabot began constructing his castle, a task he would pursue for the next 20 years. As he was building a tourist attraction and needed to draw crowds, he developed a persona as a Wild West showman–handling rattlesnakes and teaching chuckwallas circus tricks. He was possibly the only artist ever to display a sign that read: Snake Pit, Art Gallery and Museum.

His energies were divided between writing newspaper columns, working on the Pueblo, hosting Easter sunrise services, founding the first VFW, and entertaining tourists and Hollywood celebrities from the nearby B-bar-H guest ranch. While he would seem to be a thundering extrovert, his inner-hermit often reasserted itself. The host sometimes offended dinner guests when he left the table to spend evenings alone, says Maron.

In 1945, he married Portia Fearis Graham, a traveling lecturer who shared his interest in Theosophy. When she and Cabot met, she was teaching at a metaphysical school in Morongo.

It’s hard to see how Cabot ever had time to paint, given the work of building his fortress of four stories, 150 windows and 65 doors. The artist toted cement, rocks, sand, shovels and picks. He hauled timbers, glass and wood from abandoned homesteaders’ shacks, as well as the Colorado River Aqueduct construction camps.

California art historian Nancy Moure once described the completed Pueblo as “a folk environment along the lines of a bottle house or a hubcap village.”

Cabot imagined his village filling up with artists. In a crayoned blueprint of the construction discovered by Maron, Cabot had labeled two small rooms: Artist bays. He labeled another building: The Studio.

Many of the artists who visited were from Laguna Beach, then a thriving art colony and the part-time home of Cabot’s mother, Nellie. Western artist Burt Procter stayed at the Pueblo on weekends and purchased nearby land from Cabot for a home he planned to build.

Artist Roy Ropp came out from Laguna with his wife, Marie. (The two later founded Laguna’s Pageant of the Masters.) Marie Ropp would turn out to be a key figure in desert art, operating The Little Gallery in the Desert in Desert Hot Springs before moving to Palm Desert to serve as director of the Desert Magazine Art Gallery.

While the artists came and went, Moure says, “Cabot disappeared for weeks at a time to return with canvases depicting the Cahuilla Indians.”

Another group of Pueblo regulars hailed from the art outpost of Cathedral City, where interest in Theosophy and other mystical threads was also taking hold. By looking at Agnes Pelton’s guestbook and Cabot Yerxa’s guestbook, we can see that Agnes (an increasingly well-known Cathedral City artist) visited Cabot; and Cabot visited Agnes. Burt Procter shows up in both books, as does Cathedral City artist Matille Prigge Seaman and gallery owner Marie Ropp.

After Cabot died in 1965, the Pueblo deteriorated and became an official eyesore. The City of Desert Hot Springs was prepared to bulldoze the structure before a man named Cole Eyraud stepped in and purchased the home. Thanks to the late Eyraud, the house on Miracle Hill was saved. Now owned by the City, the Pueblo is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Cabot’s art colony never fully materialized and his art never brought him fame. When newspaperman Harry Lawton interviewed the pueblo-builder in 1956, he wrote: “There’s an aching disappointment in Yerxa’s soft-spoken voice when he speaks of art.”

If you visit the Pueblo today, you’ll notice a few of Cabot’s paintings on the adobe-mix walls. The Museum’s art holdings include rolled linen paintings brought back from Paris, $1 postcard paintings Cabot sold at the Garnet train station, large kachina paintings (the weathered originals have been replaced by copies) on the outer walls of the Pueblo and a sketchbook with charming watercolor scenes of early Desert Hot Springs ranches and homesteads.

“We have only a small fraction of his output, apparently,” says historian Richard Brown. “His best work might be treasured in various private homes and not available to the public.”

Cabot’s ultimate contribution was not as an artist so much as a catalyst for artists who followed. It was in those early pre-pueblo days–when Cabot lived as a hermit in a hillside dugout–that he and Carl Eytel modeled the simple ways other artists would emulate. There were few roads, no neighbors, no phones and no money. Both men were drawn to the Cahuilla and Hopi cultures; both learned from the rattlesnakes, red racers and tortoises they met on their treks. Cabot even made some of his own paints from desert clay and plants.

It’s an enduring archetype. Today we have artists constructing LED-lit homestead shacks and erecting site-specific installations that dwarf the Joshua trees. Even so, every true desert artist ultimately owes a debt to Carl and Cabot: The humble, eccentric desert rats seeking the mysterious forces whirling beneath the sand.

If you own a Cabot Yerxa painting, or can fill in details of his career as an artist, please get in touch with Cabot’s Pueblo Museum or this website.

For more on Cabot’s life see On the Desert Since 1913, edited by Richard E. Brown, and other books available at the Museum store. You can also pick up Barbara Maron’s booklet Cabot Yerxa: A Life in Art.

Excellent story!

Another really interesting and inspiring story about desert painters.

The Pueblo was one of our first forays into the desert mystique upon our arrival in 1970. Having no experience in the south, we were dazzled. Thank you for giving so much life to this story!

i would prefer a “world” with more cabot yerxa’s, dear ann, thank you for sharing his sincerity of life, a treat for me. glenda

Great article, thank you. I discovered Cabot’s Pueblo staying in Desert Hot Springs this month, and fell in love with the place and Cabot’s life story. What a fascinating person.